Quite reasonably, he observes that other EU member states would not reopen treaties because they feared that would lead to a fragmentation of the club. They would never reverse the EU's "theology" of ever closer union, he says.

But then Lawson goes on to express a belief that the British public would not fall for a minimal renegotiation of terms, similar to the limited concessions won by Harold Wilson before the 1975 referendum. "The British public is much more sceptical", he says. "I don't think they're going to be taken in by Wilsonian make-believe".

There lies the complacency, for the sham of the negotiations was as transparent then as any deal that might be offered in 2017, or some time never. But the fact of the transparency did not stop 249 Conservative MPs voting for the deal on 9 April 1975, as opposed to the eight who voted against, and the 18 who abstained. By contrast, 137 Labour MPs voted for, and 145 against, with 33 abstentions. The Conservatives carried the day.

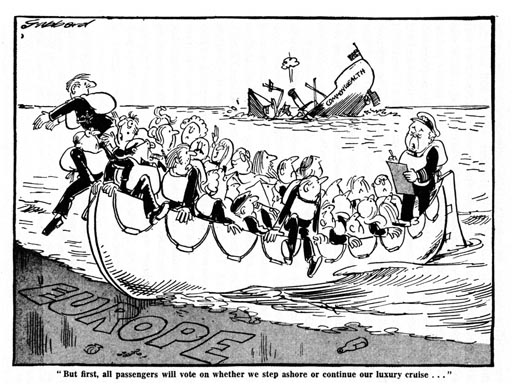

I don't accept the comfortable fiction that people were somehow deceived into believing that this was about a trading arrangement. The above cartoon in the Guardian of the time (27 February 1975) perfectly illustrates the mood. People (and especially Conservative MPs) believed what they wanted to believe, and "Europe" was seen as a refuge from otherwise unresolvable problems.

The capacity for self-delusion has by no means changed and if, in 2017 (or whenever) the whole of the establishment and the media is urging acceptance of whatever "deal" is on offer, the British public will just as readily vote to hold onto nurse. Lawson drastically underestimates the electorate's fondness for make-believe.

Thus, in a competent piece on politics.co.uk we see its editor Ian Dunt argue that: "No real eurosceptic can support Cameron's referendum".

The premise here is that prime ministers only call referendums when they are fairly certain they will win. Cameron's course of action is aimed to keep us in the EU and, should he win – as he is most likely to, if there is ever a vote – it will kill off Britain's chances of leaving the EU for a generation.

That much would have been true, but increasingly it is looking uncertain that Mr Cameron and his Conservative Party will be elected to office at the next general election, in which case the prospect of referendum is remote. The chances of Ed Miliband offering us one is zero.

The more I think about this, though, the more I am drawn to my original view that an in-out referendum would be a bad idea, simply on the basis that, under any of the circumstances currently anticipated, I cannot see us winning it.

Developing the theme I was exploring earlier, one has to concede that a referendum alone is not enough. For us to have any reasonable chance if winning, we must also have the government enthusiastically supporting an exit, and prepared to campaign for it.

The essence here is that leaving the EU is not simply a matter of "tearing up our membership card", but of completely changing the way we are governed, and our direction of travel as a nation.

In exploring our transition from a post-war independent nation to a supplicant, seeking entry to the then EEC, the official historian Alan S. Milward writes of the "rise and fall of a national strategy". He points out that it was not until the existing strategy of maintaining independence collapsed that the government could countenance joining the European treaty organisation that was to become the EU.

Similarly, it is not until the current strategy of engagement within the EU collapses that we will see a successful attempt to leave. A change in strategy must come first – the action then follows. We must go through much more trauma before we get to the desirable situation where a government is prepared to do this.

Most of all, what we need is the vision of where we are going. The Guardian cartoon shows so aptly "Europe" as the safe haven for the survivors of the sinking ship "Commonwealth", but if we were now to show "Europe" as the foundering vessel, what word or words would be written on the beach?

Until we can answer that question convincingly, the terrors of leaving a sinking ship are as of nothing compared with fears and uncertainty of embarking on a journey into the unknown. There is our task: to put different words on that beach.

COMMENT THREAD