Looking briefly at the CoE, this is based in Strasbourg, and even to visitors it often attracts little attention. Apart from the fact that it has a better staff restaurant – and some useful overspill facilities - we didn't take a great deal of notice of it when we were in Strasbourg. Even though it was connected to the European Parliament by a bridge, and we often passed through it on the way to our offices, it was just "there", a relic of the past, of little importance.

To look at it in that way was and in a mistake. The Council of Europe (CoE), bearing the same ring of stars which was later stolen by the European Union, is a powerful institution in its own right. Its problem is that it is entirely under the shadow of the EU, but it should not be underestimated. It acts in a very different and much more subtle (i.e., less visible) way.

For a start, the Council of Europe, itself a treaty organisation, is a treaty factory, having brokered 214 treaties including its founding statute which came into force on 3 August 1949.

What might surprise people, as well as the sheer number, is the breadth of these treaties. In additional to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms – to give it its full title - (and its various protocols) we have such things as the European Convention on Social and Medical Assistance and the European Agreement on the Abolition of Visas for Refugees.

We also have the European Social Charter, the European Convention on the Control of the Acquisition and Possession of Firearms by Individuals, the European Convention for the Protection of Animals for Slaughter, and even the European Agreement on the Restriction of the Use of certain Detergents in Washing and Cleaning Products.

More recently, we have the Council of Europe Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime and on the Financing of Terrorism, the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, the Council of Europe Convention on the counterfeiting of medical products and similar crimes involving threats to public health, and the European Landscape Convention.

Careful study of the list, and an examination of the recitals of many EU directives indicates that much of the EU law, about which we and our politicians complain, owes its origin to Council of Europe treaties and their protocols. Perversely, even if we left the EU, we would be bound by many provisions which cause friction, unless we also abrogated many of the CoE treaties.

But, to cast the reach of the CoE (or the EU for that matter) simply in terms of its treaties and (in the case of the EU) its formal laws, is entirely to miscast the way the international system works. What is emerging as the system matures and become more complex is a phenomenon – well known to international lawyers as "soft law", which is increasingly dominating our lives.

The EU agency Eurofound defines soft law as is "the term applied to EU measures, such as guidelines, declarations and opinions, which, in contrast to directives, regulations and decisions, are not binding on those to whom they are addressed".

Despite that lack of legally binding effect, says Eurofound, soft law may impact on policy development and practice precisely by reason of its lack of legal effect – rather, because it exercises an informal "soft" influence. Member States and other actors may undertake voluntarily to do what they are less willing to do if legally obligated. Soft law, therefore, is sometimes presented as a more flexible instrument in achieving policy objectives.

In the CoE context, it was Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)5 which has cast as "soft law" by the European Parliament Directorate-General for Internal Policies, which nevertheless called it "a significant soft law commitment on rights of LGBT persons". The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights(FRA) thought the recommendation provided "useful guidance" to EU Member States for improving the respect, protection and promotion of LGBT rights.

While soft law may not be legally binding, it often creates powerful political pressure, to the extent that it can become politically binding, in a sense. To read through the background to Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)5 tells its own story, giving a strong impression of this being the tip of the spear, with a huge momentum behind it.

As to its effect on Mr Cameron, I am warming to the view that the Recommendation was indeed pivotal in bringing the gay marriage to Parliament yesterday.

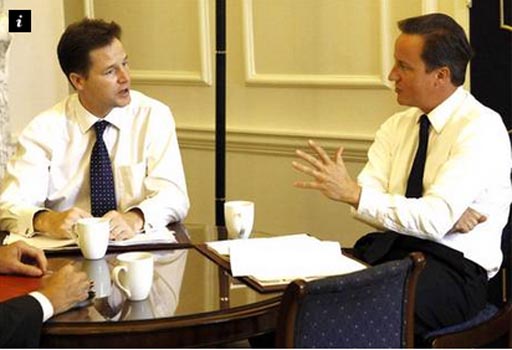

Looking at the sequence of events, we have already established that there was no intent to introduce homosexual marriage in the coalition work programme of June 2010 and we can see from the media record that, as late as September 2010, Cameron was in talks with his deputy prime minister (pictured below), having refused to consider same-sex marriages.

Then, in December 2010, we see new that gay rights campaigners planning to file a case with the European Court of Human Rights as part of an "Equal Love campaign", arguing that they are being discriminated against because of their sexual orientation.

Then, strengthening the effect of Recommendation CM/Rec(2010), we start seeing numerous instances throughout Europe where it is being considered an exemplar or amplifier of Article 8 of the ECHR (right to a family life).

Politically, this placed Mr Cameron in an incredibly weak position, as he had committed in opposition to scrapping the Human Rights Act. Now, potentially, he was facing an dangerous challenge from the ECHR which could force him to overturn his policy on gay marriage. The political effects of that could have been devastating.

Thus we see, in March 2011 the government for the first time giving a commitment to implementing Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)5, the outcome of which meant that Cameron had to introduce homosexual marriage.

Making a virtue out of a necessity, he thus made implementing the Recommendation the centrepiece of the British Chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers, at the Council of Europe. And the rest, as they say, is history.

In all this of course, no one can put their hand on a law or other directive, which forced Mr Cameron to introduce homosexual marriage. But the sequence of events, and the circumstances, provide powerful evidence that the "soft law" of Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)5 was indeed the "tip of the spear" which backed him into a corner, driving him to put his signature on a new Bill.

Soft law indeed it may be, the soft centre at the heart of darkness, but just because it is "soft" doesn't mean it doesn't work. A smothering pillow is soft, especially when compared with the casing of a bullet, but it can be just as deadly.

COMMENT: "GAY MARRIAGE" THREAD