In the incredibly limited space allowed him, he starts in 2010 with three main players, the Home Secretary Theresa May, our former Lib Dem equalities minister, Lynne Featherstone, and that shadowy institution, the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, with its controversial adjunct, the European Court of Human Rights.

In March 2010, ministers from the 47 countries represented in the Council of Europe agreed a "Recommendation" on "measures to combat discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity".

Section IV focused on Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, guaranteeing "respect for family life". It proposed that where national legislation recognised same-sex partnerships, these should be given the same legal status as those between heterosexuals.

There was no mention of marriage as yet, except in a proposal that "transgender persons" should be entitled to "marry a person of the sex opposite to their reassigned sex".

Four days before the 2010 general election, the Tory party issued a pamphlet, signed by Theresa May, in which a section on "lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender [LGBT] issues" promised that the party would "consider the case for changing the law to allow civil partnerships to be called and classified as marriage". But this was not in the manifesto, nor, after the election, in the Coalition Agreement.

In June that year, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that, though there was no obligation on countries to recognise same-sex partnerships, Article 8 did not specify that the right to enjoy family life applied only to couples of different sexes, it could be taken as equally applying to same-sex couples.

Crucially, the court proposed that, when a "consensus" emerged among the member states, this could allow the right to same-sex marriages to be recognised under the convention.

Shortly afterwards, Lynne Featherstone, the equalities minister, set out new guidelines allowing "religious music" to be used in civil partnership ceremonies. She suggested that this should be regarded as a step towards allowing gay marriages. In September, the Lib Dem party conference backed her call for same-sex marriages to be legalised.

Then, in December a campaign group, Equal Love, helped a group of British same-sex couples to launch an action in the ECHR asking for civil partnerships to be given full marriage status. They were supported by Peter Tatchell, who told the BBC that banning gay people from marriage sent "a signal that we are regarded as socially and legally inferior".

The campaign – with much conferring behind the scenes between ministers and gay lobby groups – was under way. In March 2011, May and Featherstone issued an official work programme, "Working for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Equality: Moving Forward".

It committed the Government to work "with all those who have an interest in equal civil marriage" on how "legislation can develop". Furthermore, it committed the Foreign Office and the new Gender Equality Office to work for "full implementation" of the Council of Europe’s 2010 Recommendation, with a target date of June 2013.

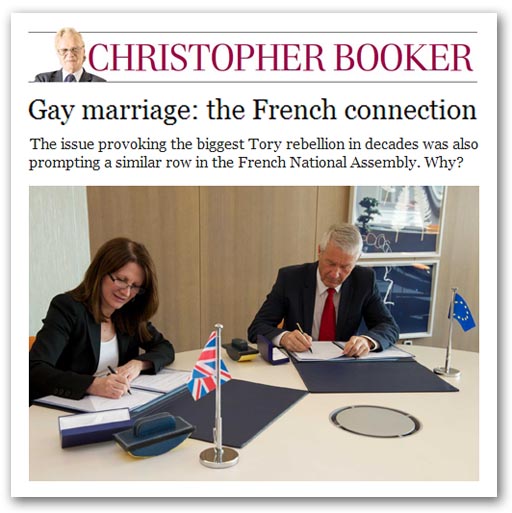

In November 2011, when Britain took over the six-monthly chairmanship of the Council of Europe, it put this at the top of the agenda. Featherstone had already committed £100,000 of government money to creating an LGBT unit in Strasbourg to plan implementation of the policy, which she formalised in a grand signing ceremony with Thorbjørn Jagland, Secretary General of the Council of Europe, on 27 March last year.

That same date, the UK's representation in Strasbourg organised the Council's first "closed conference" (ie, public not admitted), to agree detailed plans for the June 2013 implementation, with a keynote address from Featherstone.

A speech by the British judge, Sir Nicolas Bratza, then head of the European Court of Human Rights, signalled that the court was ready to declare same-sex marriage a "human right", as soon as enough countries fell into line.

The court, he said, had found that "the recognition in national law of same-sex relationships had, by our present day, reached a degree that justified a broader understanding of family life as that term is used in Article 8 of the Convention".

Such are the real reasons that our Government needed to rush through last week's vote on gay marriage. We are committed to "full implementation" of the Council of Europe's policy no later than this June (and hence the similar law now being rushed through in France).

It had been a brilliant political coup by the gay lobby, aided by Featherstone, May and those shadowy European bodies that, in so many ways, now rule our lives.

In a mischievous conclusion, Booker asks what we weren't told more honestly and openly why this had all happened, but even then the reasoning does need spelling out.

For that, we have to go back to 2009 when, in opposition, Mr Cameron had pledged to repeal the Human Rights Act. This "cast iron promise" had gone the same way as his Lisbon Treaty referendum promise, leaving him politically vulnerable every time the ECHR made a judgement that adversely affected the UK.

With Tatchell engineering a case in the ECHR, and the Council of Europe Recommendation adding to the corpus of opinion that was signalling to the court that member states were prepared to accept gay marriage, it must have been obvious that the Court was gearing up to rule in favour of the LGBT lobby.

The timing of any judgement would have been close to the 2015 general election, putting Cameron in the embarrassing position of having to conform to a highly contentious judgement at the same time he was seeking re-election.

Thus, if it was going to happen better it was to do it early, mid-term, and get it out of the way. Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)5 was the tip of the spear, and triggered Cameron's action. This was "soft law" in action, exerting its effect. It swung the balance of convenience and made something that was probably going to happen anyway happen that bit quicker.

COMMENT THREAD