With a degree of profound weariness, one also observes this newspaper telling us that the survey result raises "fundamental questions about its (the EU's) democratic legitimacy", as if it had any democratic legitimacy to start with – which it doesn't.

Strangely, though, we also have a situation where this Eurobarometer survey does not seem to have been published, with the Guardian, in collaboration with other leading newspapers in the other five countries, claiming exclusive rights – even though none of the others give the story the same prominence as the British counterpart.

Thus we have to trust the europhile Guardian accurately to inform us of a survey which is about – oddly – trust of the European Union, with the further handicap of the data having been analysed by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), which also has not published any details.

With that, we are led to believe that, "Euroscepticism is soaring to a degree that is likely to feed populist anti-EU politics and frustrate European leaders' efforts to arrest the collapse in support for their project".

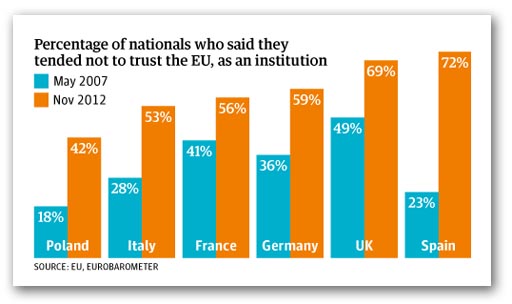

As to the detail (above), in Spain, trust in the EU – however measured and analysed - fell from 65 to 20 percent over the five-year period while mistrust soared to 72 from 23 percent. In five of the six countries, including Britain, mistrust prevailed over trust by sizeable margins, whereas in 2007 – with the exception of the UK – the opposite was the case.

Five years ago, 56 percent of Germans "tended to trust" the EU, whereas 59 percent now "tend to mistrust". In France, mistrust has risen from 41 to 56 percent. In Italy, where public confidence in Europe has traditionally been higher than in the national political class, mistrust of the EU has almost doubled from 28 to 53 percent.

Even in Poland, which enthusiastically joined the EU less than a decade ago and is the single biggest beneficiary from the transfers of tens of billions of euros from Brussels, support has plummeted from 68 to 48 percent, although it remains the sole country surveyed where more people trust than mistrust the union.

In Britain, the mistrust grew from 49 to 69 percent, the highest level with the exception of the extraordinary turnaround in Spain.

Citing José Ignacio Torreblanca, head of the ECFR's Madrid office, the Guardian goes on to tell us that, "The damage is so deep that it does not matter whether you come from a creditor, debtor country, euro would-be member or the UK: everybody is worse off". And thus we learn that: "Citizens now think that their national democracy is being subverted by the way the euro crisis is conducted".

And now we get input from José Manuel Barroso, who said on Tuesday that the European "dream" was under threat from a "resurgence of populism and nationalism" across the EU. "At a time when so many Europeans are faced with unemployment, uncertainty and growing inequality, a sort of 'European fatigue' has set in", he complains, "coupled with a lack of understanding".

What is then rather worrying is that Mr Barroso then asks, "Who does what, who decides what, who controls whom and what? And where are we heading to?" Frankly, if he doesn't know, who on earth does?

All of this, though, is enough to get Raedwald's juices flowing, as he notes – from the tenor of theGuardian's comments - a more serious malaise, in that the Left seems to have fallen out of love with the EU.

The problem, however, is even greater than it at first seems, judging from the ideas offered by the writers from the six leading newspapers to help redefine the union.

What strikes one from these is the poverty of ambition, as the ideas range from stopping the Strasbourg shuttle, to providing a Eur-app to having a Europe FC United. Then we have a suggestion that the launch of a European Army is a good idea (a plan dating from the 1950s), and the invention of "a new division of power", to deal with the "democratic deficit".

Startlingly, from Adam Leszczyński, of Gazeta Wyborcza, in Warsaw, all we get is that, "Europe needs a leading idea that could provide Europeans with symbols and aims evoking emotions, attachment and solidarity". But, adly for the poor dear, he does not know what such an idea could be. But "if we do not find it, every crisis will threaten this impressive building with destruction", he says.

It's time to move in the demolition contractors, methinks.

COMMENT THREAD