He then reiterated his view, expressed previously, that it was not in our national interests to be in the Single Market like Norway: "just accept all the rules of the Single Market, pay for the privilege of being part of it and, as it were, be governed by fax rule".

Thus do we see the perpetuation of the canard which the prime minister introduced into the debate last December, an issue that even the House of Commons Library is getting wrong. In its briefing note on "Norway's relationship with the EU", published yesterday, it wholly incorrectly declares that, "Norway has little influence on the EU laws and policies it adopts".

This basic error arises from a failure to understand the way law is made, and a very limited view of the legislative process, where only the end stage is looked at. It is only at that end of the process, the tip of a huge iceberg, that finished law emerges - much, much more has gone on before the law reaches that stage.

At the European Union level, the law includes the Directive, Regulation and Decision. The formal processes are well known and the procedures are open and visible. For instance, a Directive undergoing the co-decision procedure, requiring approval by the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament, will most often start its formal life as an official "communication" from the Commission, in what is known as the COM (final) series.

This document will comprise a detailed explanatory narrative and the text of a proposed law. It will go before the European Parliament in a series of steps and, separately, through the Council of Ministers. Both bodies will agree their "common position" and, if there are differences between them, there are procedures by which they might be reconciled.

At the end of the procedures, if successful, agreement will be reached by both parties and the approved text will be formally lodged in the Official Journal as law, thus becoming part of the acquis communautaire.

A Directive will then require transposition by the legislatures of the Member States and the EEA members, to be implemented in those territories. Regulations, of course, take direct effect, and apply once they are "done" at Brussels.

It is the nature of these formal processes which give rise to the claim that EEA members are subject to the so-called "fax democracy". They are not formally represented on the primary decision-making bodies, the Council and the Parliament, nor even the formal committees of the Commission, and thus are not able to vote on proposals.

However, while this is the visible end, the greater part of the law-making process is diffuse, obscure and very often invisible. Thus there is not and cannot be any single mechanism for exerting influence, no single protocol and no single route, by which legislation is shaped. The situation is complex, nuanced and highly variable, exactly reflecting real life and the realities of politics – which are complex, nuanced and highly variable.

Commentators who look at only part of the process, and in particular the visible, formal part of the law-making process managed by the European institutions, have thus come away with a completely false picture.

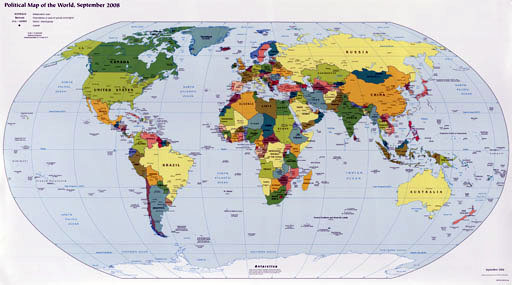

Crucially, it must be appreciated that, in a global trading environment, most of the rules governing trade do not originate with the European Union. Increasingly, they are originated or agreed at higher levels, either at global or regional (supra-EU) level, through international treaty bodies.

One of the most important is the World Trade Organisation (WTO), its mission being the supervision and liberalisation of international trade. It came into being on 1 January 1995 under the Marrakech Agreement, replacing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which goes back to 1948.

The WTO, though, represents only the tip of a gigantic iceberg. Many of the standards-setting international bodies act under the aegis of the United Nations. Furthermore, trade orientated law is often supplemented by the work of international trade bodies and standards organisations.

The output of these bodies has been termed "quasi-legislation". It is not law, per se, but is the root of law. To be implemented, it must be turned into legislation and bedded into an enforcement and penalty framework, the conversion of which is the job of regional bodies such as the EU and individual national states. Because of the international origin, and the output requires two bodies (at least) in the passage to law, it has been termed "dual-international quasi-legislation", abbreviated to "diqule".

The reach of the diqule is phenomenal. For instance, the most important banking rules, governing the conduct of the international banks, emanate as "diqules" from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. International food standards are often initiated as diqules – which are then adopted regionally and locally. These are determined by the Codex Alimentarius.

Other examples include agricultural issues, which are handled by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, taking the lead on matters affecting agriculture, forestry, fisheries and rural development. It also co-ordinates implementation of the 1992 Earth Summit's Agenda 21.

Since disease knows no boundaries, animal health controls come from the Office International des Epizooties (OIE) – created in 1924. Traffic in protected species is regulated in the first instance by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES). Human health standards and the controls and monitoring of infectious disease are determined by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Labour laws are devised by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) which was set up in 1919, by the Versailles Treaty .

At a global level, environmental issues are determined and co-ordinated by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and Climate Change issues are agreed through the aegis of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine pollution by ships is dealt with by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), which came into being in the wake of the 1912 Titanic disaster and spawned the first international safety of life at sea - SOLAS - convention, still the most important treaty addressing maritime safety.

Rights and responsibilities of nations in their use of the world's oceans, establishing guidelines for businesses, the environment, and the management of marine natural resources, are dealt with by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Aviation the province of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), created in 1944, now comprising 191 members. It claims for its mission, safe, secure and sustainable development of civil aviation through the cooperation of its Member States.

Under the aegis of IACO is the Air Navigation Commission, which considers and recommends, for approval by the ICAO Council, Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) and Procedures for Air Navigation Services (PANS) for the safety and efficiency of international civil aviation.

There is even an International Committee for Weights and Measures (abbreviated CIPM from the French Comité international des poids et mesures) consists of eighteen persons from Member States of the Metre Convention (Convention du Mètre) appointed by the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) whose principal task is to ensure world-wide uniformity in units of measurement by direct action or by submitting proposals to the CGPM.

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (French: Conférence générale des poids et mesures - CGPM) is the senior of the three Inter-governmental organisations established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre Convention (Convention du Mètre) to represent the interests of member states.

Initially it was only concerned with the kilogram and the metre, but in 1921 the scope of the treaty was extended to accommodate all physical measurements and hence all aspects of the metric system. In 1960 the 11th CGPM approved the Système International d'Unités, usually known as "SI".

These global organisations are supplemented by regional bodies, such as the 56-member United Nations Economic Commission Europe (UNECE), which for historical reasons includes the United States.

It is responsible, inter alia, for most of the technical standardisation of transport, including docks, railways and road networks. It also deals with the very detailed technical harmonisation of vehicle construction and safety standards. With UNEP, it administers pollution and climate change issues, and hosts regional agreements.

Another important regional body, often forgotten in the shadow of the EU, is the Council of Europe. Against the EU's 27 members, it has a membership of 47 European countries. Over term, it has agreed 214 treaties including its own founding treaty and, most notably, the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR).

Then there are huge number of single-issue treaty and non-treaty bodies, which set standards or agreements, or influence the global agenda, from which rules emerge and which are then implemented by signatories directly, or via groups such as the European Union, the latter acting as a law processing factory on behalf of its Member States.

Just one, and a rather arcane example of this type of body is the "Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety" (IFCS). This describes itself as "an alliance of all stakeholders concerned with the sound management of chemicals", claiming to be a global platform where "governments, international, regional and national organisations, industry groups, public interest associations, labour organisations, scientific associations and representatives of civil society meet to build partnerships, provide advice and guidance, and make recommendations". The IFCS thus describes itself as "a facilitator, advocates systemising global actions taken in the interest of global chemical safety".

A more formal but equally arcane body is the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). was established by the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, provides a protection system for the intellectual property rights of plant breeders. The Convention was adopted in Paris in 1961 and it was revised in 1972, 1978 and 1991. UPOV's mission is "to provide and promote an effective system of plant variety protection, with the aim of encouraging the development of new varieties of plants, for the benefit of society".

Arcane though this might be, after the accession of the EU to the Convention in 2005, it is driving the EU agenda on the intellectual property rights on plants. Norway, incidentally, became a member on 13 September 1993, leading rather than following the EU.

The rules produced by this plethora of international bodies are formalised long before they reach the EU institutions. When they are adopted by the EU and published as formal proposals by the EU Commission, it is invariably too late to make any changes. Any chance of influencing the rules by then has long gone.

Most of such rules are passed by the Council and Parliament without a debate and without a formal vote. In the rare instances where there is a vote by the Council, it is by QMV, where it is difficult to block a measure. Even then, the rules themselves cannot be changed unilaterally by the EU. Where international agreements are involved, votes in Council can only reject or accept proposals.

Yet these are the very rules which have already been agreed at a higher international level, negotiated by individual countries, on an intergovernmental basis, many of which can be vetoed at that level. That is where the influence counts.

Thus, it is important to be involved at this stage, to shape the rules before they become formalised, at a stage when they can be shaped, advanced and even rejected. And it is this arena that Norway is fully involved. Not constrained by the "little Europe" of the 27-country European Union, it is able to operate as a fully-fledged global actor.

Thus, the relationship between Norway as an EEA member and the EU is far from one of a supplicant to a greater power. Norway plays a very active part in the international community, and is heavily involved in the framing of international law, much of which is then adopted by the EU.

While Norway often has freedom of action, as long as we are isolated in the EU – shackled to "little Europe" - we have less control than we would like over the formulation of these "diqules". Whether it is technical standardisation of transport requirements from UNECE, common banking rules from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, international food standards from Codex Alimentarius, the animal health requirements from OIE - or labour laws from the ILO - we usually defer to the "common position" decided by the EU.

Decoupling from the EU and thus the process of political integration, and re-engaging with the international community, would allow us to restore our status and resume our proper role on the international stage, breaking free from "little Europe" and rejoining the world. That would place us alongside Norway which enjoys that freedom already.

And that is the way to look at leaving the EU. We are breaking free of "little Europe" and rejoining the world.

COMMENT THREAD