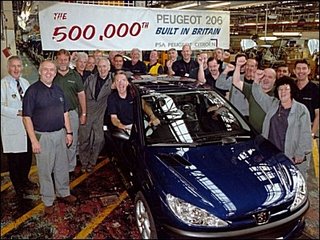

It was only just over a year ago that Peugeot pledged that its plant in Ryton, near Coventry, would play "a key role in the company's manufacturing strategy". It would, said company officials, "become the main European production site for the car for several years to come".

It was only just over a year ago that Peugeot pledged that its plant in Ryton, near Coventry, would play "a key role in the company's manufacturing strategy". It would, said company officials, "become the main European production site for the car for several years to come". Yesterday, however, union officials were called to a meeting with the firm's chief executive, Jean Martin Folz, where it was disclosed that a detailed study had been carried out at the start of 2006, the results of which showed the Ryton plant to have high production and logistical costs. This meant, said Folz, that the group was unable to justify the investment needed for the production of future vehicles.

Despite the government having offered £14.4 million towards the cost of developing the plant in order for it to deal with more than one model, and having also provided funds towards collaborative R&D projects involving Peugeot, the plant is to close next year with the loss of the 2,300 jobs of those directly employed. Many others, who rely on the plant, will fall by the wayside.

The production of a new model, it seems, it to go to Slovakia, where wages are said to be one fifth of those paid to British workers, but the key political question being asked is why the British factory, rather than one of the French plants, is being closed down.

Derek Simpson, general secretary of the union Amicus declares that, "it is inconceivable that workers on this scale would be laid off on this scale." Somewhat illogically, he then argues that "weak labour laws are allowing British workers to be sacrificed at the expense of a flexible labour market", unconscious of the fact that the jobs are being exported to a country where labour laws are even weaker.

But it took the economics correspondent of the BBC to point out that this is what happens if you allow foreign – and especially European – ownership of key manufacturing enterprises. Given an unfavourable economic wind, it will always be the plants on the periphery that go first.

But it took the economics correspondent of the BBC to point out that this is what happens if you allow foreign – and especially European – ownership of key manufacturing enterprises. Given an unfavourable economic wind, it will always be the plants on the periphery that go first.This may be an inevitable part of the general process of globalisation – and, in the short-term – is a direct consequence of EU enlargement, for which we are paying so dearly – but the closure has broader implications.

With BAE Systems pulling out of Airbus, what confidence can we have that assurances made about the continued employment of British workers will be honoured? And while the withdrawal of Airbus manufacturing would have profound economic implications, this is only the half of it.

If, as is rumoured, BAE Systems are planning to pull out of missile-maker MBDA, the prospect of strategic defence manufacturing facilities being withdrawn from Britain must surely be on the cards, and any assurances to the contrary must be about as believable as those given to Ryton workers by the Peugeot management last year.

Since we have already seen BAE Systems dismantle Royal Ordnance factories and transfer production offshore, we have no guarantees that what is happening at Ryton will not also happen to the rump of our British-based defence production.

Pledges, as we are finding, are one thing – guarantees are another. And when the last remnant of defence production moves offshore and they switch off the lights in the very last British factory, what will we do then?

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.