"A wit, raconteur, bon vivant and unflinching believer in a united Europe, had a remarkable career in the largely anti-European - if not anti-foreign - postwar British civil service." So starts the review of Roy Denman's book, The Mandarin's Tale in the unashamedly Europhile European Affairs.

"A wit, raconteur, bon vivant and unflinching believer in a united Europe, had a remarkable career in the largely anti-European - if not anti-foreign - postwar British civil service." So starts the review of Roy Denman's book, The Mandarin's Tale in the unashamedly Europhile European Affairs.Others have been less laudatory as Denman, who died on 4 April, is one of those men for whom Eurosceptics have reserved a particular detestation, a man who, while a civil service member of Edward Heath's team, was heavily involved in negotiating Britain's entry to the EEC and then who went on to join the commission, rising to become head of the commission delegation in Washington in the 1980s.

The obituary today, in The Telegraph, therefore, has to steer a course between giving homage to the deceased and conveying in neutral terms the career of a man who is widely reviled.

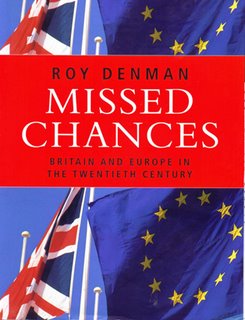

By and large, it succeeds, describing Denman as having the reputation "of an extremely able, hard-working, colourful and idiosyncratic negotiator", and author of Missed Chances: Britain and Europe in the twentieth century (1996), in which he reviewed the history of Britain and the Continent in the 20th century. The Telegraph describes him thus:

For Denman, Britain's posture towards Europe post-1945 created a catalogue of missed opportunities. The nation suffered from delusions of grandeur, a failure to recognise "the greatest secular decline in power and influence in Europe since that of seventeenth century Spain".In this book, Denman perpetuates the myth that Britain walked out of the early negotiations to form the EEC, on which he bases much of his subsequent "missed chances" thesis, one which is neither accurate nor borne out by the historical record.

There was also a failure to find bureaucrats who could, or would, operate within the new European language of compromise and administrative decision. "Brussels," Denman believed, "must be made as attractive to those seeking public service as India and the Sudan once were."

Britain's approach, he thought, only damaged the nation's influence and interests. Those who drafted the Treaty of Rome had explicitly anticipated "fiscal, social, monetary and ultimately political union", and Denman considered that this was something that British politicians had never fully understood. For his own part, he was prepared to sacrifice a certain measure of independence for a more influential role in Europe.

In 2003 he said: "We are happy with a trading arrangement, a common market. But we will not count until we make a political commitment. We have never faced up to the fact that we would have to trade power for power."

Yet, to support his colourful description of this, in his terms, tragic occurrence, Denman cites events that never happened and contradict the accounts of people who did observe the early negotiations which led to the Treaty of Rome.

For a European Union which takes great delight in pointing up "Euro-myths" which misrepresent its actions, Denman, therefore, was the perpetrator of one of the most fanciful Euro-myths of them all, one of the many on which the fictional account of the EU's history is based.

Nevertheless, Denman maintained his support for the EU to the end, writing frequently to newspapers and taking part in programmes and debates in support of the construct which, in the latter part of his career, had provided him with a good living.

His reputation as a debater, however, was much overrated – as my colleague can attest – and he never really moved on from the old paradigms on which the EU was originally based, living, like the organisation he supported, in the past.

It is not uncommon to say of people recently deceased, that "they don't make them like that now", and this is probably true of Denman, to which one can only add: thank goodness.

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.