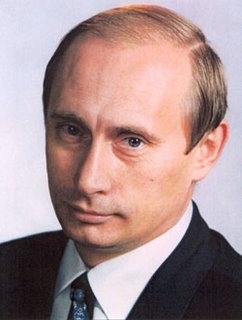

As usual, it is a little hard to read the tea-leaves as far as President Putin is concerned. Some things seem straightforward. He is determined to make Russia into a great power again the only way he knows how: by making her into a strong power, militarily by preference, as an economic bully if that doesn’t work. And, of course, it is necessary to create a strongly controlled internal regime for the purpose.

As usual, it is a little hard to read the tea-leaves as far as President Putin is concerned. Some things seem straightforward. He is determined to make Russia into a great power again the only way he knows how: by making her into a strong power, militarily by preference, as an economic bully if that doesn’t work. And, of course, it is necessary to create a strongly controlled internal regime for the purpose.To this end he has used the fact that Russia’s oil and gas supply gives the country a strong bargaining power to achieve a greater position than the overall economy of the country would warrant. The pinnacle of that achievement was the extension of the G7 to G8, thus placing Russia among the supposedly most developed countries in the world.

The G8, whose summit will take place in St Petersburg next week, serves little purpose in the modern world and its membership can be argued over. But there can be little argument about Russia’s part. As Yevgeny Volk, the director of the Heritage Foundation outpost in Moscow and the President of the Hayek Foundation in Moscow pointed out in a recent talk he gave at the International Policy Network, Russia does not qualify for G8 membership either by the size of its GDP or GDP per capita. As for economic freedom, Russia comes in at no 122, while the other 7 are all in the top 25.

The trouble is that Putin’s eagerness to establish a single economic and defence area, roughly speaking where the Soviet Union was (though the loss of the Baltic republics has been accepted) has not been greeted with complete elation – not for Putin those referendums where 99 per cent of the population votes for accession to the “elder brother’s country”.

In fact, two of the most important of the former Soviet states, Ukraine and Georgia, have shown themselves particularly independent minded, have withstood the bullying and have received Western support – reluctantly from the EU and most of its members and more enthusiastically from the United States.

As the International Herald Tribune reports, 10 days before the G8 summit, President Bush welcomed Georgian President Saakashvili in the White House. The latter had come from what has been described as a “tense meeting” with President Putin.

Georgia may well play a crucial part in the developing energy and security structure. The country is a candidate for NATO – seriously backed by the United States – and an important part of the transit route for energy supplies that come from Azerbaijan to Turkey and thence to European countries. The plan is for Georgia and others to diversify its sources of energy supplies, not to have to depend too much on Russia.

Inevitably, this causes friction with Big Brother on the border:

“Georgia's role in the wrangling over energy came into focus in January after Russia cut gas supplies to Ukraine over a price dispute, rattling West Europeans, who depend on Russian gas. When explosions in southern Russia later that month severed gas pipelines and a main electricity cable to Georgia,European speculation that Russia might be using energy as a weapon grew stronger. While Moscow said terrorists were behind the blasts, Saakashvili blamed the explosions on a deliberate Russian attack.On the other hand, Saakashvili has also given a reasonable and not unsympathetic summary of Russia’s predicament:

"There was nothing new for us in that situation," Saakashvili said, noting that Russia had switched off gas supplies to Georgia during the winter in 2000 "because of Georgia's lack of cooperation on Chechnya." Georgia has since sought to diversify its energy sources.”

“"Russia is in the process of defining itself," he said. "They are a resurgent power and they want to know how they can express themselves. Is it at the expense of dominating the policy of their neighbors? Is it by using energy muscle? Or is it, as I would think, to modernize itself, to invest in education and infrastructure, to really make Russian investment competitive?"”Like most countries, Russia defines herself in opposition to someone else and, usually, it is the West. Presumably, this is what prompted Putin to try to reach out to the various Islamic countries.

With a high proportion of Muslim population (dating back many centuries and caused by various back-and-forth conquests) it makes sense for the leader of the country to try to come to some understanding with Islamic leaders within and outside it. However, Putin has gone further.

He has been suggesting forcefully that Russia should be part of the Organization of Islamic Conference, as a major Muslim power. He has tried to explain to Islamic countries that Russia was their best friend against the West and there has been much talk of traditional Russo-Islamic friendship (not very well noted in the history books).

On a more practical level, Putin was the first non-Islamic leader to try to extend the hand of friendship to the newly elected Hamas in January and he has supported the Iranian regime’s nuclear ambitions as well as selling arms to them. Sophisticated weaponry is Russia’s other great export but whether it is sensible to sell them to Iran is questionable. There is, after all, the strong possibility that some of it may end up in the hands of Hezbollah and other jihadists, many of whom are fighting Russian soldiers in the various Central Asian republics.

Being the Islamic countries’ best friend has availed Russia nothing. Five Russian diplomats were kidnapped in Iraq and murdered, two of them, apparently, on video. Demands by the Foreign Minister Lavrov that the American troops should do more to protect diplomats were met by a cool rejoinder from Secretary of State Rice in an unexpectedly recorded exchange. She did not see why diplomats should be singled out.

Putin’s response to this and to the inconclusive and bloody conflict in Chechnya (which he re-started in 2000 for political purposes and in which the Russian have behaved with as much, if not more, brutality as the Chechen guerrillas) has been to ask the upper house of the parliament, the Federation Council, to pass legislation that would give him the right to send Russian troops abroad in pursuit of terrorists. (No mention of the UN there or of international legitimacy but let that pass.)

“The Kremlin said he had requested the right to defend "the human rights and freedoms of citizens, the sovereignty of the Russian Federation, its independence and state integrity," by using security forces outside Russia.It is not clear, whether this means troops to Iraq or just to neighbouring countries like Georgia. Nor is it clear whether the United States will welcome the sudden appearance of Russian special forces in Iraq, bent on their own agenda, which is unlikely to include a peaceful settlement. That, after all, would mean rising oil production in that country, which, in turn would mean falling prices and a deleterious effect on that 7 per cent annual growth in the Russian economy.

Under the constitution, Mr. Putin must get permission from the Federation Council, which usually does his bidding, before sending troops abroad.

Federation Council Speaker Sergei Mironov had said two days ago that the chamber was ready to authorize Mr. Putin to use special forces and the agents of the GRU army intelligence service outside Russia.”

Meanwhile there is the G8 summit next week and for that President Putin has been indulging in Potemkin techniques.

Some of it is a direct copy, as the Wall Street Journal Europe [subscription only] points out today in its article “Putin-led campaign seeks to revitalize St Petersburg". The second capital, the President’s own birth place has been given a rejuvenating and revivification treatment with many buildings restored and various large companies, such as OAO Vneshtorgbank, the second largest bank by assets, the shipping company OAO Sovkomflot and the long-distance phone monopoly, OAO Rostelekom, encouraged to move there from Moscow.

Some of it is a direct copy, as the Wall Street Journal Europe [subscription only] points out today in its article “Putin-led campaign seeks to revitalize St Petersburg". The second capital, the President’s own birth place has been given a rejuvenating and revivification treatment with many buildings restored and various large companies, such as OAO Vneshtorgbank, the second largest bank by assets, the shipping company OAO Sovkomflot and the long-distance phone monopoly, OAO Rostelekom, encouraged to move there from Moscow.Tax incentives are bringing in foreign investors but there is no getting away from the fact that St Petersburg is also a city of great poverty and rising crime, particularly racist crime. It has been argued that the income from the various large companies, such as the OAO Gazprom’s oil unit, will not do anything for the city, merely for the company’s own business centre. Clearly, this will provide employment to many local people, which is not to be discounted and that will help the economy of St Petersburg to grow. But the social problems of inadequate housing, education and health care, with old buildings crumbling away, unseen by western visitors, will remain.

President Putin’s other great Potemkin-like endeavour is the large conference of NGOs at which he intends to speak, to tell the world that, despite the legislation put into place early this year, which has forced NGOs to re-register and has tied them all up very securely by red tape and threats of legal proceedings if they step out of line, Russia is a country of freedom for civic activity. Just as in the good old days of the Soviet Union, the large international NGOs, such as Oxfam, Greenpeace and many others, have fallen for the propaganda and will attend the conference.

Others, including the Russian Memorial, who, prudently, will attend one day, have decided to set up their own alternative NGO meeting, “The Other Russia”. This is unlikely to be widely reported, no matter what the attendance might be. In fact, it is likely to have many obstacles put in its way.

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.