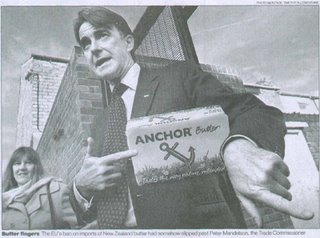

For some strange reason – conspiracy apart – the Sunday Telegraph has chosen not to upload the Booker Column onto its website this week. That is a great pity as, with three good Euro stories – including the background to the Anchor butter affair, these should have been given some prominence. Therefore, we have published the whole column here, the first story headed: "Mandelson fixes it for Anchor":

For some strange reason – conspiracy apart – the Sunday Telegraph has chosen not to upload the Booker Column onto its website this week. That is a great pity as, with three good Euro stories – including the background to the Anchor butter affair, these should have been given some prominence. Therefore, we have published the whole column here, the first story headed: "Mandelson fixes it for Anchor":In a bizarre episode which has highlighted an extraordinary internal blunder by the European Commission, it seems the Sunday Telegraph (and, therefore, this blog) may, unwittingly, have helped save the New Zealand butter industry. Last week our front-page carried a shocking report that the Commission had suspended New Zealand's right to export nearly a third of its butter production to the EU.This last story is especially interesting as it points up the hitherto unnoticed EU dimension in the home condition survey. Once again, the elephant in the room has deposited a huge pile of ordure in our midst, and no one wants to admit it.

This high-handed action had precipitated a serious crisis for New Zealand, since 14,000 tons of butter, with a retail value of £50 million, were already in transit or in bond, and would all now have to be destroyed.

The Sunday Telegraph's story, passed on through me from my collaborator Dr Richard North's EU Referendum, mentioned the name of Peter Mandelson, as EU trade commissioner – who immediately responded with a fierce denial that he had been in any way involved in this decision, stating that it had been taken by the Commission's agriculture directorate.

This in itself was remarkable. The ban directly flouted the special arrangements allowing New Zealand to export butter to the EU, negotiated when Britain joined the Common Market in 1973, and these had been confirmed under WTO rules as recently as 2001 by Pascal Lamy, Mr Mandelson's predecessor as trade commissioner (and now head of the WTO). If Mr Mandelson was not consulted on such an important EU trade issue, why not?

The story now became more curious still. Under the treaty, all New Zealand butter exports to the EU go through Fonterra, a London firm which uses the brand name Anchor. A German company, aggrieved that it was not able to import directly, raised this "monopolistic practice" with the European Court of Justice, which ruled last December that the arrangements must be changed.

But in its provisional judgement the ECJ also emphasised that, until new arrangements were in place, the existing ones must stand. When the ECJ confirmed its judgement two weeks ago, the Commission's agriculture officials made two crashing errors. First, they imposed an immediate ban, ignoring the ECJ's insistence that the existing arrangements must remain.

Second, they failed to consult with Mr Mandelson's department, even though, on a major international trade issue, it should have been centrally involved. When, therefore, Mr Mandelson's name was mentioned in the Sunday Telegraph, his officials went into overdrive - as a result of which, on Wednesday, they were able to announce that the ban had been lifted.

Those 14,000 tons of Anchor butter can continue on their way into British shops and New Zealand’s exports are safe for the future (to the huge relief of the New Zealand press): all because Mr Mandelson was so stung at being wrongly blamed for the blunder that he has now got it rectified.

******

Few actions of John Major's government have drawn such criticism as the decision, when the railways were privatised in 1994, to split ownership of the track from that of the trains running on it (hence Railtrack). Last week the Tories' transport spokesman Chris Grayling admitted that this had been a mistake, suggesting that they should be reintegrated.

This inevitably revived the question raised several times in this column over the years as to what part was played in this decision by a 1991 EC directive, 91/440, ruling that track and trains in the EU must be put under separate management, transposed into UK law by the 1992 Railways Regulations. I could never track down final proof that one thing led to the other, but I recently thought I might have found the "smoking gun" in a paper published by the Institute of Economic Affairs from Professor John Hibbs, who at the time was a senior official of British Rail.

Professor Hibbs recalled being summoned to Number Ten to advise on the privatisation, and said that he urged the selling off of British Rail to regional companies, each with its own track and trains. He was given to understand that "John Major favoured the idea" but that "Malcolm Rifkind,as minister of transport, had turned it down because of an EU ruling that operations and infrastructure had to be separated".

I raised this with Sir Malcolm Rifkind, who recalls that he personally favoured keeping track and trains in the same ownership. But the Treasury disagreed, on the grounds that this would not allow for competition between operating companies.

It may well be that Sir Malcolm is personally let off the hook, but Professor Hibbs is adamant that the EC directive played its part in shaping the attitude of Rifkind's officials and the Treasury, and that this was what he was told by Number Ten, when they rang him, following his visit, to explain why his advice could not be taken.

Certainly the way in which our railways were privatised conformed with the directive, which we were the first country in the EC to pass into national law. The problem the Tories now have to resolve is whether they can ignore that reading of the directive, if and when they ever get the chance to undo the mistake made by their Party 12 years ago.

******

Last January I wrote here that Mr Prescott's plans to introduce Home Information Packs were a "disaster waiting to happen". I had been led to this view by a reader, Philip Collings, formerly the IT director of Railtrack, who, after analysing the Government's scheme, was so convinced it would fail that he set up a website to explain why.

In recent months so many experts have joined the chorus that the Government last week bowed to their arguments, by withdrawing one of two key components of HIPs, the compulsory "home condition report", for reasons outlined here six months ago.

But the chief reason why Yvette Cooper, the minister responsible, was pushed into this highly embarrassing U-turn was alarm in the Treasury (where her husband Ed Balls is a minister) that HIPs would plunge the housing market into chaos. A collapse in house prices would deal a devastating blow to the UK economy (valued at more than £3 trillion, domestic property is now the largest single asset underpinning its strength).

Among several reports analysing how this might come about was one compiled by my property consultant son Nicholas, showing how the introduction of HIPs in three phases, with a 70 percent shortfall in the number of inspectors needed to compile the home condition reports, would produce a hopeless mismatch of supply and demand, lasting up to 18 months This, when the Bank of England is warning that homes are overvalued by 30 percent, would lead to a massive downward "correction" of the market (his report is available from in2perspective.com).

But the Government is still having to persist in a cut-down version of its cockeyed HIPs scheme, thanks to an EC directive making it mandatory for homes to be marketed with an "energy efficiency certificate". When I reported this last January, Ms Cooper wrote denying that this was why the Government was introducing HIPs. Yet she now admits that this is why HIPs cannot simply be withdrawn altogether.

As usual, the Government has indulged in "gold-plating", going considerably further than the directive requires by forcing anyone who sells or rents out a home to pay £200 for a few virtually meaningless sheets of paper. But even in their reduced form, this means that HIPs will introduce needless complications into buying and selling. They may have reduced the chances of plunging the housing market into chaos - but don't rule it out.

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.