For some months now, we have been following the increasingly surreal saga of the EU's "unintended" ban on lead organ pipes, through the combined effects of the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) and the Restriction on Hazardous Substances Directives.

For some months now, we have been following the increasingly surreal saga of the EU's "unintended" ban on lead organ pipes, through the combined effects of the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) and the Restriction on Hazardous Substances Directives.While this saga seems to be coming to a messy end, with the likelihood that church organs will escape the ban – an issue which Booker will deal with in this Sunday's column – it has focused our minds on the broader impacts of these directives and, in particular, the Restriction on Hazardous Substances Directive (RoHS), about which, so far, we have written very little.

This, it turns out, has been a major omission on our part as, with the Directive coming into force on 1 July, only now is it emerging that this will be imposing billions of pounds in extra costs to industries throughout the world, to deal with a non-existent threat, and increasing the harmful impact on the environment. In short, while there is no shortage of examples of harmful EU legislation, this directive must qualify as one of the most, if not the most egregious example.

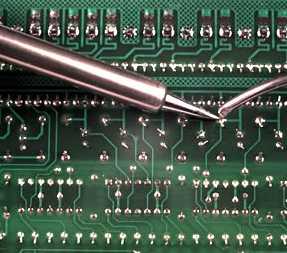

The particularly damaging aspect of this new law which, to give it its full name, is Directive 2002/95/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment, is the ban on the use of lead in electronic equipment, thus prohibiting the use of lead-based solder.

It is transposed into UK law as The Restriction of the Use of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronic Equipment Regulations 2005, linked with the WEEE Directive. And therein does the trouble start.

Although the WEEE Directive aims at increasing the amount of recycling of electronic equipment, the EU commission has decided that a significant volume of this waste will still be landfilled and some incinerated, while much will be handled in recycling centres. With the equipment containing metals such as mercury, cadmium and chromium, the RoSH Directive claims these, "would be likely to pose risks to health or the environment".

Although the WEEE Directive aims at increasing the amount of recycling of electronic equipment, the EU commission has decided that a significant volume of this waste will still be landfilled and some incinerated, while much will be handled in recycling centres. With the equipment containing metals such as mercury, cadmium and chromium, the RoSH Directive claims these, "would be likely to pose risks to health or the environment".Thus, says the Directive, "the most effective way of ensuring the significant reduction of risks to health and the environment relating to those substances" is the substitution of those substances in electrical and electronic equipment by safe or safer materials." Restricting the use of these "hazardous substances", it adds, "is likely to enhance the possibilities and economic profitability of recycling of WEEE and decrease the negative health impact on workers in recycling plants."

So it is that the Directive bans the substances listed from use in a wide range of electrical and electronic equipment and while there may – and I stress may – be some justification in controlling the use of some of them, there is no good evidence that the use of lead-based solder in electronic equipment is posing any threat whatsoever to the environment or the health of workers, either during manufacture or recycling, or when disposed of in landfill.

What is surprising however – although it should not be – is that, despite the claims of health and environmental threats, the latter based on the risk of lead-contaminated leachate from landfill sites, at the time the directive was being discussed, that data were largely theoretical, based largely on US studies. It was only when a number of field studies were subsequently carried out – such as this one here - examining the actual amount of lead leaching from landfill sites, that is was realised that there was no problem at all.

Especially significant was a year-long study by the Solid Waste Association of North America (SWANA) Applied Research Foundation. Released in March 2004, this concluded that heavy toxic metals, including lead, did not pose an existing or future health threat in municipal solid waste landfills.

The foundation reviewed existing research and concluded that the natural conditioins in landfill sites, such as precipitation and absorption, provide chemical reactions and interactions that prevent heavy metals from dissolving into the soil. They concluded that out of 130,200 tons of heavy metals placed in municipal landfill in 2000 from electronics, batteries, thermometers, and pigments, almost all - 98 percent - was lead. Cadmium and mercury made up the remaining amount.

According to the authors, "The study presents extensive data that show that heavy metal concentrations in leachate and landfill gas are generally far below the limits that have been established to protect human health and the environment."

By then, it was too late – the "train had left the station" and the momentum for new legislation was too great. But, by 2005, the US Environmental Protection Agency had got its act together and produced a 472-page report, assessing the full, life-cycle environmental impact of banning lead solder.

From this work, it emerged that when the impact of mining and refining substitutes was taken in to account, the higher energy consumption in using the lead-free solders, which require higher temperatures, and all the other issues were factored in, the banning of lead – far from having a positive impact on the environment (and worker health) – actually had a significant negative impact. Amazingly, though, this work had never been done by the EU and the legislation was, by then, already in place.

It was then left to member states to justify the ban, which the UK attempted to do in a series of "regulatory impact assessments", which can only be described as a parody of the genre.

In the first attempt, in 2003, The authors plaintively note:

It is very difficult to quantify the precise costs of the Directive given its complexity and scope of impact. In addition there is currently limited information available about the extent and cost of substituting the banned substances. Research and tests, which are necessary to fulfil the Directives' requirements, are still ongoing and the results are uncertain.In page after page, it was not to get any better, the report offering only the vaguest of estimates as to costs, although it did concede that Orgalime (a trade association of electronics manufacturers in Europe) had estimated a cost across Europe of €15 billion for "new investment to deal with required technological change". This, it said, "implies costs to the UK of the order of £1.7 billion", most of which were attributable to the use of lead-free solder. And that was just to deal with the changes needed to deal with new material, to which must be added to higher material and energy costs, estimated at around £200 million extra per year.

Small businesses were then considered and the view was that RoHS "could disproportionably" affect them "as they may not have the financial resources to undertake R&D projects to develop substitutes". Chillingly, the report added, "They may also find difficulty in absorbing the additional costs, to comply with the Directive." To this day, no one has the first idea of how many jobs will be lost.

As to the reduction of health risks, the official estimates were equally vague, the assessment noting that the ban "will entail a reduction in the use of certain hazardous substances in EEE and therefore should result in reductions in risks to human health and the environment." However, the report added, "it is not easy to quantify the resulting benefits."

By the time of the final assessment in 2005, the estimates had got no better, although the Department of Trade and Industry was now claiming that the overall costs in the UK would be £700 - £13000 million, with absolutely no figures attached to the benefit and no evidence offered as to whether they would be realised.

Nevertheless, the final document bears the signature box of the minister of state for energy, Malcolm Wicks, declaring, "I have read the regulatory impact assessment and am satisfied the benefits justify the costs".

On the basis of this charade, proprietors of firms not obeying this cretinous law can face unlimited fines and imprisonment yet, worryingly, there are still many serious doubts about the reliability and suitability of lead solder substitutes, so much so that military equipment has been exempted.

For the rest of us, though, courtesy of this utterly mad EU legislation, we are to pay more for less reliable equipment, with an overall greater harmful impact on the environment. There are no words sufficient to describe the utter, complete, total fatuity of a system that can allow this to happen.

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.