I doubt if it would be possible to project two more different views of the Blair project than those respectively in the Sunday Telegraph leader and in the front page Column Seven article in The Business.

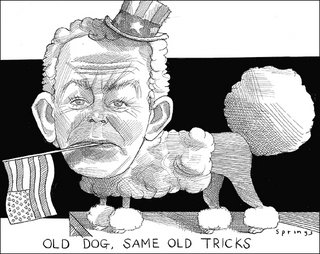

I doubt if it would be possible to project two more different views of the Blair project than those respectively in the Sunday Telegraph leader and in the front page Column Seven article in The Business.The former, accompanied by the cartoon illustrated (above), declares that, "Once again, Mr Blair puts America first", depicting the prime minister as a willing poodle of the American administration. The latter, written by this author and headed, "Euro defence market reform is integration by stealth", paints an altogether different picture – of the UK rushing, lemming-like into the arms of the European Union, as defence integration gathers momentum.

Confronted with two such diametrically opposed views and forced to chose between them, a causal observer – sated by the recent publicity on Blair's visit to Washington – might be more comfortable with the Telegraph view, especially as the continuing military adventure in Iraq constantly suggests an apparently close relationship between Bush and Blair.

However, to make the choice, it seems, is a flawed option. There is no reason why two apparently contradictory political ideas cannot co-exist simultaneously, each or either taking the headlines according to circumstances, as their advocates battle it out in less public forums. Thus, it is quite possible that, if not simultaneously, Blair can support both closer co-operation with the US administration and the idea of European defence integration.

In fact, depending on his appreciation of the two issues, and the nature of the advice he is being given, Blair may not even believe the two policy issues are contradictory. He might actually have convinced himself – or been convinced - that they are complementary, in the traditional manner of the United Kingdom forming a "bridge" between Europe and America, by keeping a foot in both camps.

On the other hand, it could be that Blair is one of those "Walter Mitty" characters who lives in a world of his own creation, detached from reality. Alternatively, he could be the sort of person that agrees with the last person who spoke to him, and chops and changes his mind with the prevailing winds or the expediences of politics.

On the other hand, it could be that Blair is one of those "Walter Mitty" characters who lives in a world of his own creation, detached from reality. Alternatively, he could be the sort of person that agrees with the last person who spoke to him, and chops and changes his mind with the prevailing winds or the expediences of politics.Dealing with the apparent conflict between the Atlanticist and the pro-EU policies, one can certainly divine from Blair's speeches and behaviour in the United States, that he is avowedly pro-US (and, more specifically pro-Bush), but if you take a longer time frame, things can look very different. Read, for instance, Blair's statement on 5 February 2003 immediately after his meeting with French president Jacques Chirac at Le Touquet.

Here, the Mr Blair that The Telegraph would have us believe is Bush's poodle, happily listens to Chirac – without demurral - telling him:

We have discussed defence. Very often we have not seen eye to eye on this between France and Britain, this is a matter of history, but I remind you that it was in St Malo that we have started, Mr Blair and I, the idea of pooling our resources, having a defence pool, and we have convinced the 13 other partners in the European Union that this was a good move. We have now reached the point where the European Union has a common defence policy which is developing apace. We have progression and this must go on…only for the prime minister to respond:

In the field of defence, it is as you know four years since St Malo and we had a difficult negotiation frankly to get the European Union and NATO in agreement together. But now that that has been resolved, I think this is the time to push that whole initiative forward, and we have agreed a number of things, as the President was indicating to you…He then goes on, amongst other things, to talk about the development of a "comprehensive approach to defence capability" with the "establishment of a new agency" in order to make sure that we are matching the aspirations that we have in European defence with capability and efficient procurement. Blair then refers to the "concept of the rapid reaction capability", making sure that "we have the ability to act quickly and deploy quickly in circumstances where we need to".

For sure, this is over three years ago but, since then, Blair's fond expressions of fidelity to Chirac have been translated into the European Defence Agency, which is at the heart of the European defence integration process, while the development and equipment of the European Rapid Reaction Force proceeds apace.

With the aid of selective quoting, therefore, a case may be made for Blair being either or both an Atlanticist or pro-EU, in which case – as I have so often cautioned – when trying to assess politicians, you look at their hands, not their lips. In other words, it is what they do, not what they say, that matters.

Here, of course, Blair's Iraq policy is seen as the most tangible evidence of US support, but there is equal validity in suggesting that his attachment to the venture was driven more by domestic electoral considerations, with him seeking to replicate the Thatcher Falklands effect. Only since the perception has taken hold, that the rapid military victory has degenerated into a debilitating counter-insurgency effort, has the campaign become an electoral liability.

Similarly, the Afghan venture is seen by some as evidence of Blair's support for Bush, but again, this is not necessarily so. The British forces in the region are not in fact working alongside the US but are part of a multinational structure that includes European forces.

On the other hand, the progress of European defence integration is tangible, some of which has been charted by myself, and more yet in a recent report by Statewatch. So much of this, though, is administrative and technical - compared with the high profile operations in Iraq and Afghanistan – that it is largely unreported by the media. It remains "under the radar". People – including the Sunday Telegraph leader writers - may, therefore, be making their judgements on the highly visible, without appreciating the extent of the less visible.

On the other hand, the progress of European defence integration is tangible, some of which has been charted by myself, and more yet in a recent report by Statewatch. So much of this, though, is administrative and technical - compared with the high profile operations in Iraq and Afghanistan – that it is largely unreported by the media. It remains "under the radar". People – including the Sunday Telegraph leader writers - may, therefore, be making their judgements on the highly visible, without appreciating the extent of the less visible.And, if the media has very little idea or understanding of what is going on, all that begs the question as to how much the politician know. Few now believe that ministers are in control and know what their departments are doing – an idea is even less prevalent after the successive debacles in the Home Office. What confidence can we have, therefore, that successive defence ministers or fully in control of their departments, or even aware of what is happening in the administrative bowels?

Here, one of the most important articles in today's newspapers – and possibly least read – is by Katharine Raymond, a former government advisor. Under the heading Step aside, Sir Humphrey, she acquaints us with the "cold reality" that most politicians are helpless in the face of a civil service that can be reluctant or inept. "Between ministers and their civil servants," she writes, "lies an unspoken truth". Both know that the politicians have no real control over their departments. She thus remembers "one testy meeting":

…when a senior civil servant told a minister his opinion "would be taken into account when we make a decision". Fireworks ensued but they did not change the fact that this particular official believed that he was the boss. Most of the time he was.In this context, we know that in the Foreign Office and indeed in Defence, there are senior civil servants who have strong Europhile loyalties, one such typified by Nick Witney who, after a spell in both departments, has gone on to head the European Defence Agency. These men – and women – undoubtedly have their own agendas and, with political leaders who have only limited control over them, are able to pursue personal and political ambitions that can be at odds with declared, headline policy.

Thus it is, without even Blair being schizophrenic - in a political sense, at least – the system itself can be, simultaneously pursuing diametrically opposed policies.

The shame is, when it comes to the Telegraph leader, its writer(s) see the need to assess the situation in such one-dimensional, black-and-white terms. They argue that the occupation of Iraq is likely to signal the end of the "Blair Doctrine" on foreign intervention, whence they look forward to Britain's international relations being "once again based on the solid foundation of national interest rather than the vapidities of international solidarity".

More probably, the absence of a countervailing pull from the United States will mean an even more decisive lurch in the direction of the EU. Instead of subsuming our "national interest" to the United States as some maintain Blair is doing, we could instead be dragged ever more into the thrall of our European "partners". And, whatever your view of the current situation, that could be considerably worse.

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.