As news comes through that the case of George Galloway seeming being economical with the truth before the Senate Sub-committee is being handed over to the Manhattan District Attorney and other parts of the US judiciary, it is worth comparing this with the random indictments of American (and some other) citizens by “trigger-happy” judges in Europe.

The latest case that is running its inevitable and useless course is the one Spanish judges have brought against three American servicemen for killing a Spanish journalist during the shelling of the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad.

The story is inconclusive and has to do with various, so far unproven, allegations that American troops have been targeting hotels with journalists in them. The Palestine Hotel was shelled by a tank unit on April 8, 2003, during the capture of Baghdad. Two journalists were killed, including the Spanish cameraman, Jose Manuel Couso Permuy and it is his supposed murder that is causing the problem with activist Spanish judges.

The American response has been that the tank unit fired at the hotel in response to firing from it and around it. Whether it is from the actual hotel that they had been fired at is immaterial – decisions taken during a battle cannot always be second-guessed in courtrooms.

But it is not the death of one particular war correspondent (a breed that tends to be in danger) that is at stake but the whole concept of legality. The judge in Madrid who had issued the arrest warrant did so because “the Americans might have committed murder and a "crime against the international community" by firing on the hotel.” The idea that any place where a journalist might happen to be in wartime is sacrosanct is a strange one.

There are two points here and both have to do with the creeping attempts made by the tranzis to grab power for which they will never be accountable. One is the rather strange notion that somehow the Iraqi war is “illegal”. Illegal by whose standards? What is this body of legal opinion that can make judgements of that kind and apply them to the whole world?

The UN is not a judicial organization and has no body of criminal law on the basis of which it can act. The International Criminal Court makes up its rules as it goes along and, again, has no single body of criminal law to refer back to. What is illegal in, say, the United Kingdom, is not necessarily that anywhere else.

A war can be intelligent or foolish; it can be justified or not; it can be aggressive or defensive or pre-emptive; it can, even, be just or unjust, though one rather wonders how many of the people who are loudly condemning the war in Iraq for its “illegality” have bothered to read St Thomas Aquinas on that subject. But what a war cannot be is illegal, because there is no legality to break.

But as Eric Rosenberg of Hearst Newspapers says about the Spanish case and the Italian attempt to extradite 22 supposed CIA operatives for allegedly kidnapping an Islamic cleric from Milan (if we are talking about international legality, what about the story of the Italian Red Cross using its privileged position to smuggle known terrorists through American military check-points):

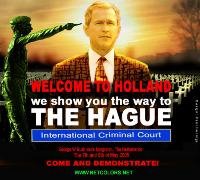

“Both cases underscore a trend among some European judges: stepped-up use in the past three years of a legal principle known as universal jurisdiction, the view that governments have the right to try anyone accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed anywhere in the world.”

What precisely is universal jurisdiction and on what basis do European judges claim the right to administer it? American response has been that no American citizen can, according to the Constitution, be tried by a foreign court, though, naturally, there are extradition treaties. Consequently, the United States has refused to participate in the International Criminal Court and refused to acknowledge European judges’ rights over their citizens. Not surprisingly the universal jurisdiction principle is never directed against people, such as President Mugabe and many others who have committed many a crime against humanity, but inevitably against American, British and Israeli politicians.

Not surprisingly the universal jurisdiction principle is never directed against people, such as President Mugabe and many others who have committed many a crime against humanity, but inevitably against American, British and Israeli politicians.

“It's the same legal principle Spain employed in seeking the extradition of ex-Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet from England and a Belgian court used when it sought to put Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon on trial for a massacre committed by Lebanese militias in Lebanon in 1982.

The principle has been used liberally against senior American officials, straining bilateral relations with U.S. allies.

In 2004, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, former CIA Director George Tenet and other officials were named in a criminal complaint filed in a German court on behalf of four Iraqis who alleged that American forces mistreated them at the at Abu Ghraib prison.Belgium has been a favorite venue for such lawsuits. Courts there have allowed lawsuits alleging human rights crimes by Vice President Dick Cheney, Army Gen. Tommy Franks, who led the 2003 invasion of Iraq, former Secretary of State Colin Powell and former President Bush.”

No wonder they took so long to bring the paedophile murderer Marcel Dutroux to justice.

The Belgian efforts lasted only as long as Defence Secretary Rumsfeld started musing about actions and consequences, the possibility of moving NATO headquarters from Belgium or blocking some of the money for the existing buildings. The accusations were swiftly watered down and, in any case, even Belgian judges decided that the legal aspects were rather dodgy. The lawsuits were thrown out.

The principle, if it can be called that, has been taken up by Italian and Spanish judges. If one compares the Spanish case in particular with the Galloway case, we can see the difference between what is true legality and what is phony legality masking a power grab by over-ambitious lawyers and transnational organizations.

This is not to say that one can predict how the Galloway case will end. But the accusations are very specific and easily defined. The man was on oath, said various things and there appear to be several lots of documents that show him to have perjured himself. That is a felony in the United States and in most other countries. The papers from the Senate sub-committee have gone to various judicial bodies in America and copies have been sent to the House of Commons.

There are other papers that the Volcker Commission used to come to very similar conclusions. These are all definite matters – the alleged felony and the evidence.

The accusations levelled at the three American servicemen are, on the other hand, vague and impossible to prove, not least because the crime they are accused of is non-existent. According to this the presence of international journalists in a war zone makes it impossible for the combatants to act as that becomes a crime against the international community.

Behind that legal mumbo-jumbo is political activism – another attempt to impose irresponsible and unaccountable transnational power over responsible national authorities. And, strangely enough, all this judicial activism is always directed against democratic states.

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.