We've been giving defence quite a good airing lately, so I was reluctant to devote another long post to the subject, for fear of stretching the patience of our readers.

We've been giving defence quite a good airing lately, so I was reluctant to devote another long post to the subject, for fear of stretching the patience of our readers.Considerable interest, however, has been displayed in the piece by Peter Almond in The Sunday Times yesterday, headed "Beware: the new goths are coming", and, on reflection, it is too important to glide over. So here goes.

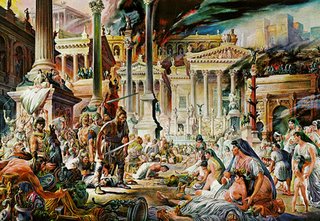

The piece records the views of "one of Britain's most senior military strategists" who is warning that western civilisation "faces a threat on a par with the barbarian invasions that destroyed the Roman empire", comparing future migrations with the Goths and Vandals, adding that north African "barbary" pirates could be attacking yachts and beaches in the Mediterranean within 10 years.

This is Rear Admiral Chris Parry's view, who suggests that Europe, including Britain, could be undermined by large immigrant groups with little allegiance to their host countries. He calls it a "reverse colonisation" by groups that stay connected to their homelands by the internet and cheap flights, making the idea of assimilation redundant.

Parry's views are important because he is head of the development, concepts and doctrine centre at the Ministry of Defence and is charged with identifying the greatest challenges that will frame national security policy in the future.

If his apocalyptic vision of a security breakdown occurs, Parry thinks it is likely to be brought on by environmental destruction and a population boom, coupled with technology and radical Islam, triggering mass migration from the Third World.

"The diaspora issue is one of my biggest current concerns," he says. "Globalisation makes assimilation seem redundant and old-fashioned ... [the process] acts as a sort of reverse colonisation, where groups of people are self-contained, going back and forth between their countries, exploiting sophisticated networks and using instant communication on phones and the internet."

Parry predicts that as flood or starvation strikes, the most dangerous zones will be Africa, particularly the northern half; most of the Middle East and central Asia as far as northern China; a strip from Nepal to Indonesia; and perhaps eastern China.

He pinpoints 2012 to 2018 as the time when the current global power structure is likely to crumble. Rising nations such as China, India, Brazil and Iran will challenge America's sole superpower status. This will come as "irregular activity" such as terrorism, organised crime and "white companies" of mercenaries burgeon in lawless areas. The effects will be magnified as borders become more porous and some areas sink beyond effective government control.

Parry expects the world population to grow to about 8.4 billion in 2035, compared with 6.4 billion today. By then some 68 percent of the population will be urban, with some giant metropolises becoming ungovernable. He warns that Mexico City could be an example.

In an effort to control population growth, some countries may be tempted to copy China's "one child" policy. This, with the widespread preference for male children, could lead to a ratio of boys to girls of as much as 150 to 100 in some countries. This will produce dangerous surpluses of young men with few economic prospects and no female company.

"When you combine the lower prospects for communal life with macho youth and economic deprivation you tend to get trouble, typified by gangs and organised criminal activity," says Parry. "When one thinks of 20,000 so-called jihadists currently fly-papered in Iraq, one shudders to think where they might go next."

The competition for resources, Parry argues, may lead to a return to "industrial warfare" as countries with large and growing male populations mobilise armies, even including cavalry, while acquiring high-technology weaponry from the West.

That, with a little more detail, is the thesis which, as far as it goes, is all good stuff. But like an appetiser without a main course, its leaves one only partially sated. What is totally absent from the Times report is any idea of how government should respond and how this affects not only defence but other policy areas.

What does come over, to those who are aware of the broader issues, is a scenario where the boundary between homeland security and defence are becoming blurred. Further, immigration seems to be moving up the agenda as a security issue, while third world development and issues such as aid seems to be a vital part of our overall security strategy.

There also seems to be a confirmation of a broader recognition that the future of conflict lies not in war between states, each fielding conventional forces, but in armed gangs and loose trans-national coalitions, acting within and across national borders, with conflict spilling over and manifesting itself as international terrorism and organised crime.

This is the future of the jihadist, where war is declared not by states but by groups of people who share cultures or political objectives – or who are simply motivated by a nihilistic hatred of other cultures. But it is a future that, in certain respect, is already with us.

That we have people like Rear Admiral Chris Parry thinking about this – with, apparently, a staff of 50 at Shrivenham, is slightly comforting, but what we do not see is how his ideas and predictions translate into policy.

If we are to deal with scenarios that he envisages, how does this equate with the current restructuring plans for the British Army? Is the expenditure of £14 billion on FRES necessarily the right way to go. If we are having to deal with an enemy in our midst, is the purchase of two aircraft carriers, which with their air groups will cost in the order of £15 billion, a sensible way of using our resources?

For that matter, is the commitment to a European Rapid Reaction Force, dedicated to intervention in as yet unspecified circumstances, against unknown objectives, at all the right way to go.

If we are going to find ourselves intervening, more in a policing role, rather than in overt warfighting, is the equipment we are buying entirely appropriate and are the force structures and training at all adequate to the projected tasks. Can we indeed maintain the traditional separation between military and civilian security forces or, as the nature of conflict blurs, will we see the distinction between the two roles also blurring?

All these and many more questions arise from Parry's efforts, but we see no overt political debate – or any intelligent discussion in the media about the fundamental issues raised. Thus, all we have is questions, questions, but no answers.

COMMENT THREAD

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.